Elderly couple still fighting for freedom after six decades

Posted: April 22, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: anti-rightist movement, China, Chinese politics, Confucianism, Confucius loyalty, Cultural Revolution, democracy, Du Runsheng, freedom, intellectuals, Mao Zedong Comments Off on Elderly couple still fighting for freedom after six decades

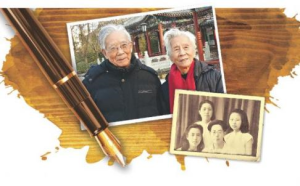

He Yanling and Song Zheng as they are today, main picture. The then Zhang Zhenghuai (bottom left) and Yang Yuzhi (bottom right) with friends as journalism students in 1944.

Photos: courtesy of He Yanling

Oppressed by the KMT in the 1940s, two students yearned for a better society under communism. Now, decades on, they remain disillusioned

When Yang Yuzhi and Zhang Zhenghuai were expelled from school in Henan in 1940, they did not realise it was only the beginning of their lifelong struggle for freedom and democracy.

Under the Kuomintang regime, 18-year-old Yang, 16-year-old Zhang and four friends formed an underground reading group to study liberal publications advocating democracy – a risky move at a time when such materials were seen as heretical and communist sympathisers were harshly oppressed.

Like many young people at the time, Yang and Zhang longed for the end of the dictatorial and corrupt KMT rule and aspired to the ideals of fraternity, freedom and equality – as championed by the Communist Party at the time.

So later, when they were studying journalism at Fudan University, then based in Chongqing during the second sino-Japanese war, they got involved in underground work for the Communist Party and helped set up a newspaper which acted as a front for clandestine communist activities.

In July 1946, with their names now on the KMT government blacklist, they escaped to the nearest communist base where they joined the newly founded People’s Daily – then operating secretly in rural Hebei .

To protect their families from persecution, they changed their names: Yang became He Yanling and Zhang became Song Zheng. They married a month later.

When the Communist Party won the civil war in 1949, the couple were ecstatic. He’s first article in People’s Daily after the establishment of the People’s Republic was entitled “From darkness into brightness”.

“We thought there would be a joint government made up of democratic parties … and we could focus on building a prosperous, democratic, civilised and happy new China,” He said in a recent interview.

But at the time, they could not have imagined that more than 60 years on, they would still be on the same mission when their hair had turned grey – after a lifetime of struggle, their dream of freedom, democracy and equality has still not been fulfilled.

Now aged 90 and 89, He and Song are among the few remaining torch-bearers of the early dreams of their generation and feel they have a responsibility to leave behind the stories of comrades who sacrificed their youth for a free China.

After their retirement, together with former journalists Mu Guangren and Tong Shiyi (who were also involved in underground work as young men), they spent nearly 20 years painstakingly researching historical archives and interviewing survivors across the country to produce three volumes of books entitled The Children of Hongyan. Hongyan was the southern communist base in Chongqing during the anti-Japanese war between 1939 and 1946.

The first two volumes, published in late 2005, recorded the stories of how idealistic students risked their lives to help spread communist ideals and garner support for the underground party during the war under KMT rule between 1939 and 1949.

The third volume, which no mainland publisher was willing to handle because of its political sensitivity, focused on the tragic fates of dozens of underground party members who became targets of countless political movements under the new government in 1949. A shorter version, Hongyan Children’s Sin and Punishment, was published in Hong Kong in 2008.

“After the liberation [in 1949], these people whom the party had nurtured became the targets of political movements,” Song said ruefully.

Many of them simply did not understand why they, who endured torture and jailing by the KMT, could suddenly be viewed with suspicion by their own party. Many were banished to hard labour in the countryside after the anti-rightist movement in 1957 and persecuted relentlessly as “enemies of the people” in the Cultural Revolution.

Then, in the course of research for the book in 2004, Mu by chance came across whisperings that it was actually Mao Zedong’s official secret policy to persecute former underground members and purge them from the party in the new regime.

Such information would have been classified as top-secret at the time but Mu was nonetheless able to confirm the authenticity of such a policy from several retired senior officials, including liberal party veteran Du Runsheng, who remembered seeing a relevant document

“And history attested to this,” said Mu. “The anti-right-leaning campaign, the anti-rightist movement, the Cultural Revolution … these were not against individuals but against the intellectuals as a group.

“This [policy] was the source of all this and there was no escape for people like us.”

In the foreword to the Hong Kong edition, He describes the poignant heartbreak of elderly people like himself who suffered tremendous physical and mental abuse during political turmoil in the past few decades, and their grief at being rejected by the party they loved.

They helped overturn an autocratic old regime, “yet what we have built is completely different from the one we had fought for”, he said, quoting Soviet writer Nikolai Ostrovsky.

“They did not care about losing their lives in the struggle against dictatorship … yet after overturning the dictatorial regime, they found it replaced by a new system where power is still highly centralised,” he writes.

He and Song said they felt a particular sense of urgency to record their former comrades’ lives, not least because many were old and frail, but also because their stories are rarely mentioned in the official narratives of the Communist Party history, which attribute the victory against the KMT to the armed revolution which was led by Mao.

“The stories of these people from the bygone democratic movement cannot be buried … and what happened to them after the liberation [in 1949] should also be passed on to the current generation,” He said.

“Noting down what they said and did is a duty to history,” he said, noting that many of their interviewees had since died.

He and Song said the contribution of underground party members has been downplayed because many had been accused of being “traitors” for signing confessions in KMT jail to protect their communist identities from being revealed.

This was used in later political movements as evidence of their collaboration with the enemy.

Their stories are still suppressed in the party’s official history, they believe, because the authorities are wary of student movements and their calls for democracy. The elderly authors lament that many of China’s problems that they had wished to rectify in their youth have not changed, but they are not yet prepared to give up their struggle.

“The problem of one-party has not been resolved, nor has dictatorship … there has been no fundamental change and the authoritarian system is still here,” said Mu.

“Therefore we still have to pursue our youthful dreams, and that is the purpose of writing the books. We have to continue our struggle. We must not forget that history.”

Yet why did those who were not afraid of torture, jail or even death for the sake of democracy under the dictatorial KMT regime later put up with persecution from their own party? And why did the once-independent-thinking intellectuals swallow their dignity to bow under Mao’s authority?

“It’s probably like one’s loyalty towards the emperor in the past – it is just as foolish,” wrote Zhao Hongcai, an underground Communist who had been jailed by the KMT, in Hongyan Children’s Sin and Punishment.

In his personal story, Zhao told of an occasion when he was sent to hard labour in the countryside in the 1950s, a peasant questioned why a righteous person like himself would be persecuted by the party, and he surprised himself by instinctively defending the party, even though he knew he was wrongly accused of being a rightist.

“No, brother, I deserve it, you can’t blame the Communist Party!” he said.

His own words pained him because “I was only doing it so that this farmer … wouldn’t think badly of the party just because I was wronged.”

Zhao was sent to hard labour for years as a “rightist” after heeding Mao’s call for honest criticisms of the party government in the 1950s.

He was later beaten and jailed during the Cultural Revolution from 1966-1976, during which he survived by begging for eight years. He died of cancer in 2003.

Zhang Lifan , a historian formerly with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said the Confucian culture of loyalty and filial piety to the emperor was still very much in the minds of the intellectuals who followed the party. Having invested their youth in the party they associated with freedom and democracy, they remained loyal even when the party had changed, he said.

“It was this traditional mind-set, as if they were courtiers serving the emperor,” he said.

In the minds of the intellectuals who dedicated their youth to the party, “Communist Party was the exemplification of democracy,” He Yanling said.

“But what they did not realise was … that it was impossible to use the instruments of war to build an idealistic society that is in line with humanity and justice,” he said.

Source: “Elderly couple still fighting for freedom after six decades”